Ovarian Cancer

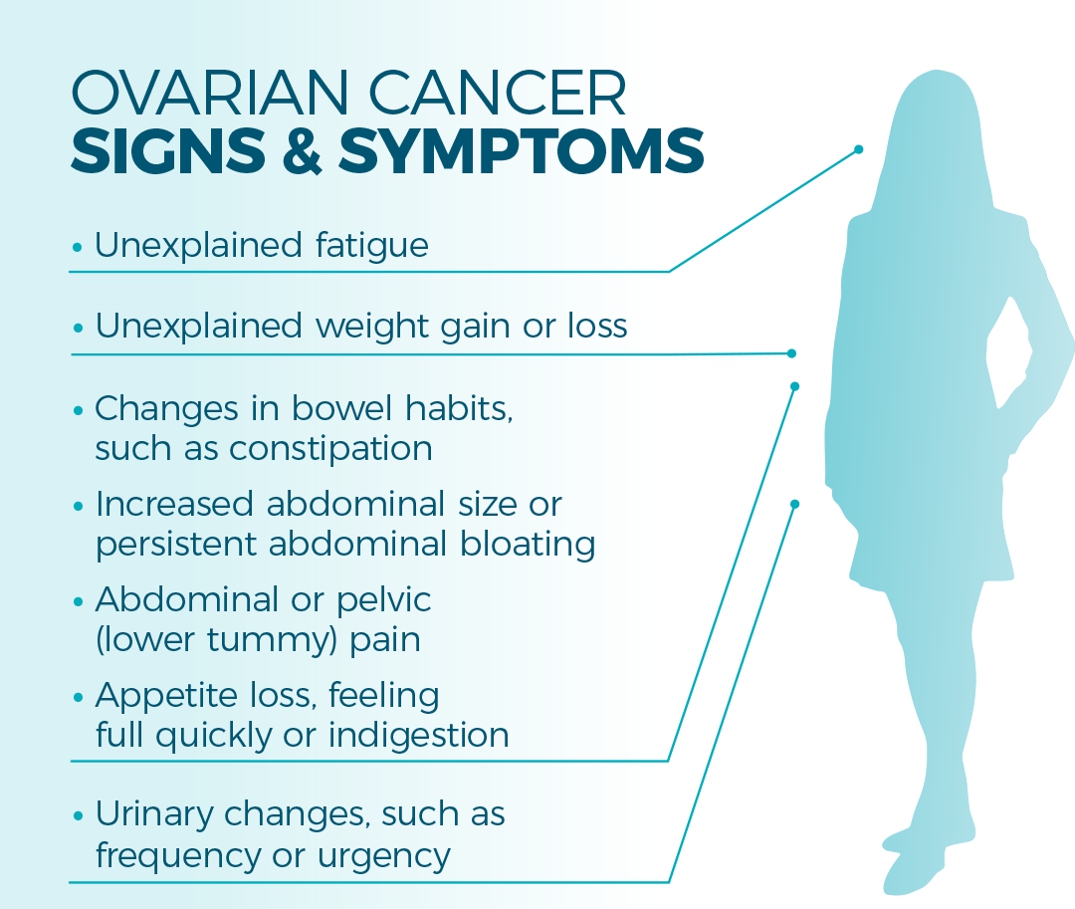

- Abdominal bloating

- Eating less and feeling fuller

- Abdominal, pelvic or back pain

- Needing to pee more often or more urgently

- Changes in bowel habits

- Fatigue

It would be easier to count the wāhine who haven’t experienced these symptoms[1] than those who have. At least individually, they could be symptomatic of any one of many health issues, both fleeting or longer term; mild or serious.

But… they all could be the symptoms of ovarian cancer.

“The symptoms of ovarian cancer are often vague and ill-defined and overlap with symptoms of much more common disorders such as dyspepsia, irritable bowel syndrome, [issues with] menstruation, and menopause. This makes early diagnosis a challenge as well.”[2]

As well as the above list of symptoms, indigestion, abnormal vaginal bleeding or discharge, unexplained weight changes and painful sex are also possible symptoms of ovarian cancer.[1]

Originally, the title of this article referenced ovarian cancer‡ as a “silent killer”. While far too many wāhine and health practitioners are insufficiently aware of the symptoms of ovarian cancer, the moniker “silent killer” perpetuates the idea that ovarian cancer is without symptoms for a prolonged period of time or not present until the cancer is advanced.

Cure Our Ovarian Cancer*, in their 2022 National Ovarian Cancer Report, write that historically, ovarian cancer was often regarded as symptomless, despite the majority of women/wāhine experiencing classic symptoms for a prolonged period of time.[3] The report goes on to say that at least one of Aotearoa New Zealand’s medical school libraries still hosts textbooks incorrectly stating that ‘most patients with ovarian cancer experience no symptoms’ ”.[3]

The idea that ovarian cancer is a “silent killer” is a myth, says Dr Barbara Goff. She says that the “more clinicians and primary-care providers recognise the early signs, instead of “blowing them off” as just gastrointestinal problems or nerves, the more lives will be saved.”[4]

“Many healthcare professionals are seemingly unaware of the symptoms typically associated with ovarian cancer, so misdiagnosis remains common,” noted Goff, in her an editorial in the Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology.[5]

This persisting belief, and the fact that many symptoms may be mistaken for other conditions, leads to frequent misdiagnosis. The National Ovarian Cancer Report says that “women/people [visit] their doctor again and again, only to be misdiagnosed”.[3] The Ovarian Cancer Foundation NZ says that common misdiagnoses include irritable bowel syndrome, constipation, urinary tract infections, menopause, gastritis and even depression, stress or needing to lose weight.[1]

Awareness of symptoms of ovarian cancer is poor among women, with as few as 14% being familiar or very familiar with symptoms, and even in a high-risk population there was a low level of awareness (24%) of symptoms.[6]

Studies have found that although health practitioners have a generally better knowledge of symptoms “knowledge deficits were still found. The inability to finish a meal and early satiety were only identified by 59% and 64%, respectively.”[6] This inadequate familiarity with symptoms among health professionals inevitably results in delays in diagnosis.[6]

Cure Our Ovarian Cancer’s 2020 survey suggests almost 50% of women/wāhine in Aotearoa New Zealand wait more than three months to be diagnosed with ovarian cancer after presenting to their doctor with symptoms, and for 20% diagnosis takes longer than 12 months.[3] This is in stark contrast to the situation in Australia, where “time to clinical diagnosis was less than 2 months for 39% of women; 61% were diagnosed within 3 months, and almost 80% were diagnosed within 6 months. Only 4% were not diagnosed until more than 1 year after symptom onset.”[7]

The survey of women/wāhine with ovarian cancer, mentioned above, also asked respondents about delays in discussing their symptoms with their doctors, and how long it took to be referred for blood tests and ultrasounds (see Diagnosis below) and how long it took to be diagnosed. Only 8% went to their doctors immediately (within one month), 44% between one and three months, and 44% took between three months and one year to see their doctor.

While 42% of women were referred for tests on their first or second doctor’s visit, 31% had three to five visits before being referred for further tests, 16% had 6-10 visits and for 11% of women they had to visit their doctor more than ten times before the doctor referred them for diagnostic tests.

Twenty-six percent were diagnosed within a month, a further 28% within three months, and a further 23% within a year; 22% of women had their diagnosis delayed by a year or more and of those two thirds were delayed by more than two years.

In another study, almost half (48%) of all women/wāhine with ovarian cancer experience an emergency diagnosis,[8] where they are diagnosed through a visit to a hospital emergency department rather than through a primary care provider. This happens despite many women experiencing symptoms for months or in some cases years, before their diagnosis. Aotearoa New Zealand has the worst emergency ovarian cancer diagnosis rates of comparable health systems in the world, and 42% of women/wāhine with an emergency diagnosis will be dead within a year compared to 17% diagnosed via primary care.[8]

Author’s note:

This article on ovarian cancer (which can also be read in pdf format or downloaded) is one of the longest and most in-depth articles published by the Auckland Women’s Health Council. It became apparent as I undertook the research for this article, as it will become apparent to readers, that it is vital that the gynaecological cancers (other than cervical cancer), get far greater attention, particularly ovarian cancer. Far too many women are either unaware of ovarian cancer or know little about the symptoms. Sadly, many GPs seem to lack sufficient awareness of the disease to respond in a timely manner and ensure prompt diagnosis in women when they do present with symptoms. Opportunities within the health system to raise awareness in both women, and their health practitioners, are being missed, and as a result many women die prematurely. The disturbing statistics on ovarian cancer in Aotearoa New Zealand justify the space we have dedicated to the disease in this edition of the Newsletter.

In this article the terms wāhine/women and female are used throughout. It is not our intent to be exclusionary and these terms are used for ease of reading a sometimes complex article. We acknowledge that not all people with ovaries identify as women/wāhine and we include transgender men, intersex and non-binary people who have ovaries in the cohort of people this article is aimed at and who are at risk of ovarian cancer.

Women/wāhine are tragically unaware of four out of five gynaecological cancers

Almost every woman/wāhine will have heard of breast and cervical cancer. These are the high-profile cancers, the ones that get all the media coverage. These are the two female cancers for which there are screening programmes. Many women don’t know that alongside cervical cancer there are four other gynaecological cancers – ovarian, uterine, vulval and vaginal. Ovarian cancer affects more women than cervical cancer does and is more deadly than breast cancer.

A 2022 survey in the UK found that 34% of people can’t name a single gynaecological cancer and only 2% of people can name all five gynaecological cancers. A subsequent survey found that only 7% of people said they had a good knowledge of gynaecological symptoms before they or a loved one experienced them.

Other research has shown that as few as 41% of people mention gynaecological cancers when asked which cancers they have heard of. Cervical cancer was most frequently mentioned (28%), followed by ovarian (12%) and endometrial cancer (11%).

In Aotearoa New Zealand, a survey of women who had been diagnosed with ovarian cancer found that 32% had never heard of ovarian cancer prior to their diagnosis, 59% had heard of it but didn’t know any of the symptoms, while only 9% knew any symptoms.[3]

Ovarian Cancer: Types, Diagnosis, Treatment

Ovarian cancer is not a single disease – there are over 30 different types and each one requires individualised treatment. Two thirds of women have high grade serous ovarian cancer, while the remaining one third of diagnoses involve one of the rarer types, such as low-grade serous, clear cell, germ cell or small cell ovarian cancer.[9] It is now believed that many ovarian cancers, including the most common high-grade serous carcinomas, frequently originate from precursor lesions in the fallopian tubes.[10], [11] This is important with regard to potential preventive approaches (see Prevention below).

The Ovarian Cancer Foundation NZ have an excellent webpage setting out more detailed information on the different types of ovarian cancer, including symptoms for each, diagnosis, risk factors, treatment (funded and unfunded), clinical trials and recurrence.

There is no screening test for ovarian cancer. Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Barbara Goff, says that “[f]or the past 25 years, scientists have tried to identify a screening test to detect ovarian cancer in its earliest stages, when the chance of cure is high. Unfortunately, multiple clinical trials with hundreds of thousands of participants have failed to identify an effective way to screen for ovarian cancer.”[12]

Unfortunately, studies have shown that some women – as many as 40% in one UK survey[13] – are of the mistaken belief that cervical smears can test for or diagnose ovarian cancer,[6] [14] but this is not the case and cervical screening is completely unrelated. Some doctors will do a physical exam at the time of a cervical smear and palpate the abdomen, which may pick up an ovarian mass, but cervical screening itself is of no diagnostic benefit in ovarian cancer.

Disturbingly, one survey of health professionals in the US found confusion about Pap smears even among clinicians “with 33% of healthcare providers incorrectly identifying an abnormal Pap test as a symptom of ovarian cancer.”[6]

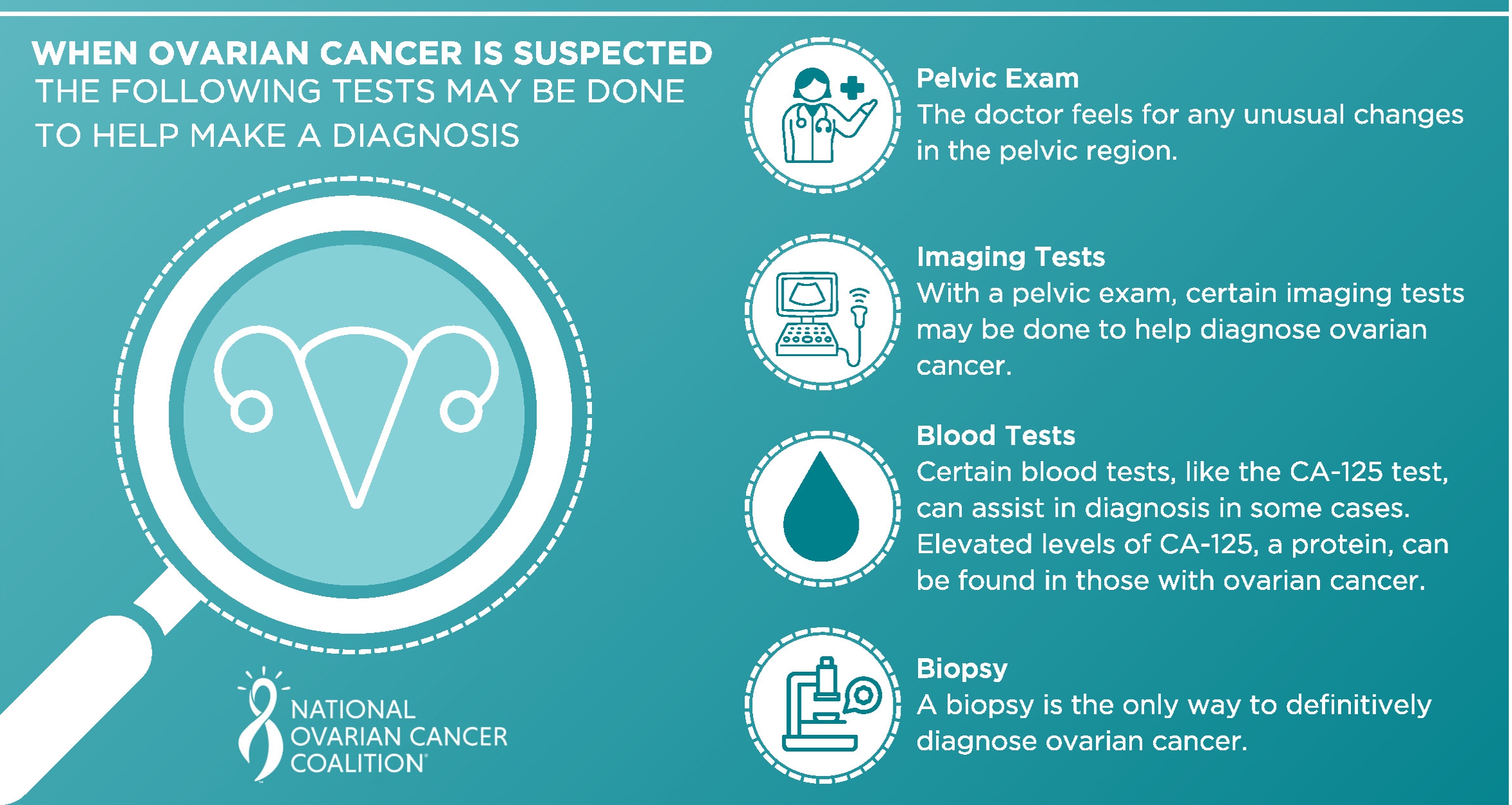

Upon presenting with symptoms indicative of ovarian cancer, a woman’s doctor will likely do a physical pelvic exam. If the doctor finds something – for example a mass or lump in the vicinity of the ovaries – they should refer a woman for further tests. However, a normal pelvic exam does not mean there is no ovarian cancer and if symptoms persist women should request further testing.[15]

Diagnosis typically involves ultrasound (usually transvaginal ultrasound) and the CA-125 blood test, which looks for a specific protein in the blood that may be elevated because of ovarian cancer.

“Ovarian cancer is more likely if the result is 35 units/mL or higher. However, most people with an elevated CA-125 result do not have ovarian cancer, and some people with ovarian cancer have a normal blood test; this is more common in younger people with ovarian cancer and early-stage ovarian cancer.”[15]

Treatment depends on the type of ovarian cancer and stage – how far the cancer has spread. Standard treatment involves surgery, with the removal of ovaries and fallopian tubes (salpingo-oophorectomy) and possibly the uterus. Other tissue and organs may also be removed if the cancer has spread.9 Surgery may be followed by chemotherapy.[16]

Other treatments include targeted drugs and radiation. Patients may also qualify for participation in clinical trials.[9]

Late Diagnosis

Ovarian cancer is one of a number of cancers that are typically diagnosed late, when the cancer has spread beyond the tissue or organ in which it originated.

Often ovarian cancer is diagnosed very late, when it has already metastasised – by the time women/wāhine present to their doctors with symptoms and are actually diagnosed, there are significant limitations on the ability of treatment to send the cancer into remission and the prognosis is often poor with limited survival time.

A 2023 study found that delays in diagnosis were contributed to by multiple factors, including:

- women’s delay in recognising symptoms and seeking care, often a consequence of lack of knowledge about early signs of ovarian cancer;

- missed opportunities during healthcare encounters, due to misattribution of a woman’s symptoms by their physicians, and underestimation by doctors of symptom severity.[14]

“Tumour stage at diagnosis is an important factor determining the patients’ survival, which is threefold higher in women diagnosed at Stage I compared to Stages III–IV. Unfortunately, most women and other people with ovaries are diagnosed with Stage III or Stage IV cancer.”[16] Studies have shown that 70 to 75% of cases diagnosed at stage III or IV where the cure rate is less than 30%.[17]

A study published in the journal Gynecologic Oncology in 2020, said that “[o]varian cancer continues to be diagnosed at advanced stage with high fatality rates. A significant contributing factor is lack of clear alarm symptoms.” The study “explored the association of symptoms, routes and interval to diagnosis and long-term survival in a population-based cohort of postmenopausal women diagnosed with invasive epithelial tubo-ovarian cancer.”[18]

The main symptoms considered were loss of appetite/feeling full, abdominal/pelvic discomfort or pain, increased abdominal size or bloating and change in bowel habit; abdominal pain, loss of appetite/feeling full, were significantly associated with increased mortality.[18]

Ultimately, this study illustrated the complexity of diagnosing ovarian cancer at an early enough stage that would improve prognosis and survival. Increasing numbers of symptoms is associated with poorer survival, as is emergency presentation to doctors or hospitals. While the study supports the need to fast track treatment, they also found that the time interval between initial onset of symptoms and diagnosis did not independently influence survival once other factors such as age, stage and type of ovarian cancer were considered.[18]

The researchers found that “to decrease deaths from ovarian cancer, it is critical we remain focussed on understanding disease biology, exploring preventative strategies, refining the current screening strategies by incorporating novel tests and optimising surgical and adjuvant treatment.” However, they could not exclude the possibility of better outcomes in those who are aware and act on symptoms compared to those who do not.[18]

A Harvard Medical School statement advises that “any woman who experiences one or more of these complaints almost daily for more than a few weeks should see a clinician for a pelvic exam.”[19]

It is critical that to improve outcomes and reduce mortality from ovarian cancer women pay attention to symptoms that do not go away fairly quickly, and insist on follow-up investigation of persistent symptoms rather than allow themselves to be “fobbed-off” or reassured by their health care professionals.

Risk Factors

Notwithstanding variations in risk factors for the different types of ovarian cancer, there are a range of non-modifiable and modifiable risk factors for ovarian cancer, and the modifiable risk factors offer some opportunities for prevention, at least at a population level.

While globally the life-time risk is only about 1 to 2%, the high mortality and low five-year survival rate makes an understanding of risk factors important in terms of both increased scrutiny of high-risk women/wāhine, and implementing whatever preventative actions are feasible.

The highest rates of ovarian cancer occur in postmenopausal women/wāhine, so age is one of the most significant non-modifiable risk factors for the disease.[20, 21]

Geographically, Dr Marliyya Zayyan writes that the highest incidence is “found among white females in Northern and Western Europe and in North America” but she makes particular note of the high incidence in New Zealand.[21]

Various studies show that approximately 20% of women with ovarian cancer carry one of the two BRCA gene mutations (BRCA1 and BRCA2), which are also responsible for a significantly increased risk of breast cancer. Sundar et al., write that by the age of 70 the lifetime risk of ovarian cancer in women with a BRCA1 mutation is as much 85%, and in women with a BRCA2 mutation it is as much as 84%.[20]

However, the majority of cases of ovarian cancer have no known genetic link.

A woman’s hormonal history has a significant impact on her risk, with the more ovulatory cycles a woman/wāhine has over her lifetime increasing her risk, a concept referred to in some of the medical literature as ‘incessant ovulation’. The hypothesis is that “that recurrent minor trauma caused to the ovarian epithelial surface as a result of ovulation increases the risk of malignant transformation.”[22] Early menarche – especially under the age of 12, late menopause, infertility or no pregnancies, all increase the number of ovulatory cycles and thus raise the risk of ovarian cancer.

Conversely, anything that reduces the number of ovulatory cycles reduces the risk of ovarian cancer, including increasing numbers of pregnancies and live births, longer duration of breastfeeding, use of oral contraceptives, and late menarche and early menopause.[20, 23, 24]

A 2017 study that investigated rates of ovarian cancer in US and Australian women of European descent found that ovarian cancer rates were increasing until the generation of women who were the first to use The Pill. Incidence then declined dramatically “such that rates for the 1968 cohort [of women] were about half those of women born 45 years earlier.[25] However, the researchers found that “incidence rates are likely to stop falling and may even increase with changes in the prevalence of other factors such as tubal ligation and obesity.” (see below)

Infertility – either because of the lack of pregnancies or because of the use of fertility drugs – has been associated with an increased risk of ovarian cancer, particularly those women who received fertility treatment but failed to conceive.[21, 24]

There is also evidence that there is a higher risk of ovarian cancer in those with endometriosis22 and pelvic inflammatory disease.[26]

There are several modifiable risk factors for ovarian cancer, including obesity (especially in post-menopausal women), tobacco use in some sub-types of ovarian cancer, and use of hormone replacement therapy (HRT).[20, 22, 26] HRT is believed to enhance oestrogen-induced proliferation of ovarian cells and therefore increase risk, and the association was found in multiple studies using different HRT formulations (e.g. oestrogen alone, oestrogen and progesterone continuously, oestrogen and progesterone sequentially).[22] One study showed a 40% increase in ovarian cancer for HRT users (which amounts to one additional case of ovarian cancer for every 8300 users);[27] 60% of ovarian tumours have been found to be oestrogen-receptor positive.[22]

The authors of a 2022 ‘umbrella’ review found “evidence that diabetes increases the risk of ovarian cancer incidence”, and that the “use of metformin was found to have highly suggestive evidence for a lower ovarian cancer risk.”[22]

From a dietary perspective, higher consumption of vegetables is associated with a reduced risk of ovarian cancer, while higher consumption of saturated fat increases risk.[26] Studies have also shown that vitamin D may offer a protective effect but the data is not conclusive at this time.26 With regard to exercise and physical activity, studies have found “a nearly 20% lower risk for the most active women compared to the least active” and that “prolonged sedentary behaviour, high levels of total sitting duration, and chronic recreational physical inactivity have all been noted to increase risk.”[26]

A more controversial risk factor, but one for which there is increasing scientific evidence is the use of talcum powder. Epidemiological evidence indicates an association with talc use and increased risk of ovarian cancer.

A 2006 meta-analysis of 21 studies found an approximately 35% increase in risk with genital exposure to talc[28], and this was subsequently confirmed in a 2016 study that found genital talc use was associated with an increased risk of 33%, with a trend for increasing risk with increasing number of years of use.[29]

Prevention

In their 2017 paper, researchers from the Moffitt Cancer Center in Florida, discuss the modifiable risk factors – personal lifestyle choices – that will make a practical difference to the chance that an average woman (with no known genetic risk factors) will develop ovarian cancer. They suggest that women wanting to reduce their risk will have between two and four pregnancies**, take oral contraceptives for between five and ten years**, will forgo the use of hormone replacement therapy for menopausal symptoms and maintain her BMI at 24 or lower. A woman aiming to reduce her risk would also breastfeed her babies, engage in regular physical exercise, and not smoke tobacco.

In 2015, the Society of Gynecologic Oncology set out recommendations for preventing ovarian cancer:[10]

- oral contraceptive use;

- tubal sterilisation;

- risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy† in women at high hereditary risk of breast and ovarian cancer;

- genetic counselling and testing for women with ovarian cancer and other high-risk families;

- opportunistic salpingectomy after childbearing is complete (at the time of elective pelvic surgeries, at the time of hysterectomy, and as an alternative to tubal ligation) for non-high risk women.

Screening for Ovarian Cancer

To date, screening for ovarian cancer is not viable. Unlike cervical screening, which can actually prevent the development of invasive cancer as well as pick up cancer early enough to cure it, studies into screening for ovarian cancer have failed to find any survival benefit.

A very large trial of 78,216 women aged 55 to 74 years investigated the feasibility of screening for ovarian cancer between 1993 and 2010.[30] Fifty percent of participants were assigned to undergo annual screening (CA-125 for six years and transvaginal ultrasound for four years), and 50% usual care, at 10 screening centres across the US. The usual care group was not offered annual screening with CA-125 or transvaginal ultrasound but received their usual medical care. Participants were followed up for a maximum of 13 years for cancer diagnoses and death until February 28, 2010.[30]

Ovarian cancer was diagnosed in 212 women in the intervention group and 176 in the usual care group; there were 118 deaths caused by ovarian cancer in the intervention group (56%) and 100 deaths (57%) in the usual care group. However, 3285 women received false-positive results and 1080 underwent surgical follow-up, of whom 163 women experienced at least one serious complication (15%).[30]

There was no statistically significant reduction in mortality from ovarian cancer as a result of the screening, yet there was significant harm caused to women who received false positives in the screening group. In addition, there was no benefit seen in stage shift – that is, diagnosis of ovarian cancer at an earlier stage that would typically result in better outcomes. In fact, the total number of advanced stage cancers was greater in the intervention group (163) than in the usual care group (137).[30]

The study researchers concluded that annual screening for ovarian cancer with simultaneous CA-125 and transvaginal ultrasound does not reduce the death rate in women at average risk for ovarian cancer, but does increase invasive medical procedures and associated harms.[30]

Unfortunately, research into ovarian cancer screening since this large study has not yielded any more positive outcomes. Presentations at the 11th Biennial Ovarian Cancer Research Symposium in 2017 demonstrated that effective screening remains elusive.[31] More recently, another very large study, conducted in the UK and involving 202,638 women, came to similar conclusions as the US study, with no reduction in mortality as a result of screening. The UK researchers concluded that population screening for ovarian and tubal cancer for average-risk women using these CA-125 testing and transvaginal ultrasound should not be undertaken.[32]

A study published in early 2024, which investigated a much smaller cohort of women (7,856) who were screened using the CA-125 blood test and transvaginal ultrasound, found a marked stage-shift with more cancer being detected earlier; however, this research did not investigate the impact on mortality from ovarian cancer.

Internationally, there are currently no recommended screening programmes.[33, 34]

Ovarian Cancer in Aotearoa New Zealand

In Aotearoa New Zealand, ovarian cancer is the sixth most prevalent cancer among women/wāhine (behind breast cancer, colorectal cancer, lung cancer, melanoma and uterine cancer) and with similar rates to Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma.[35, 36]

However, the death rate from ovarian cancer is very high compared with other cancers; it competes with pancreatic cancer for ‘honours’ as the fourth biggest cancer killer in women/wāhine. Like ovarian cancer, pancreatic cancer has often metastasised by the time it is diagnosed.

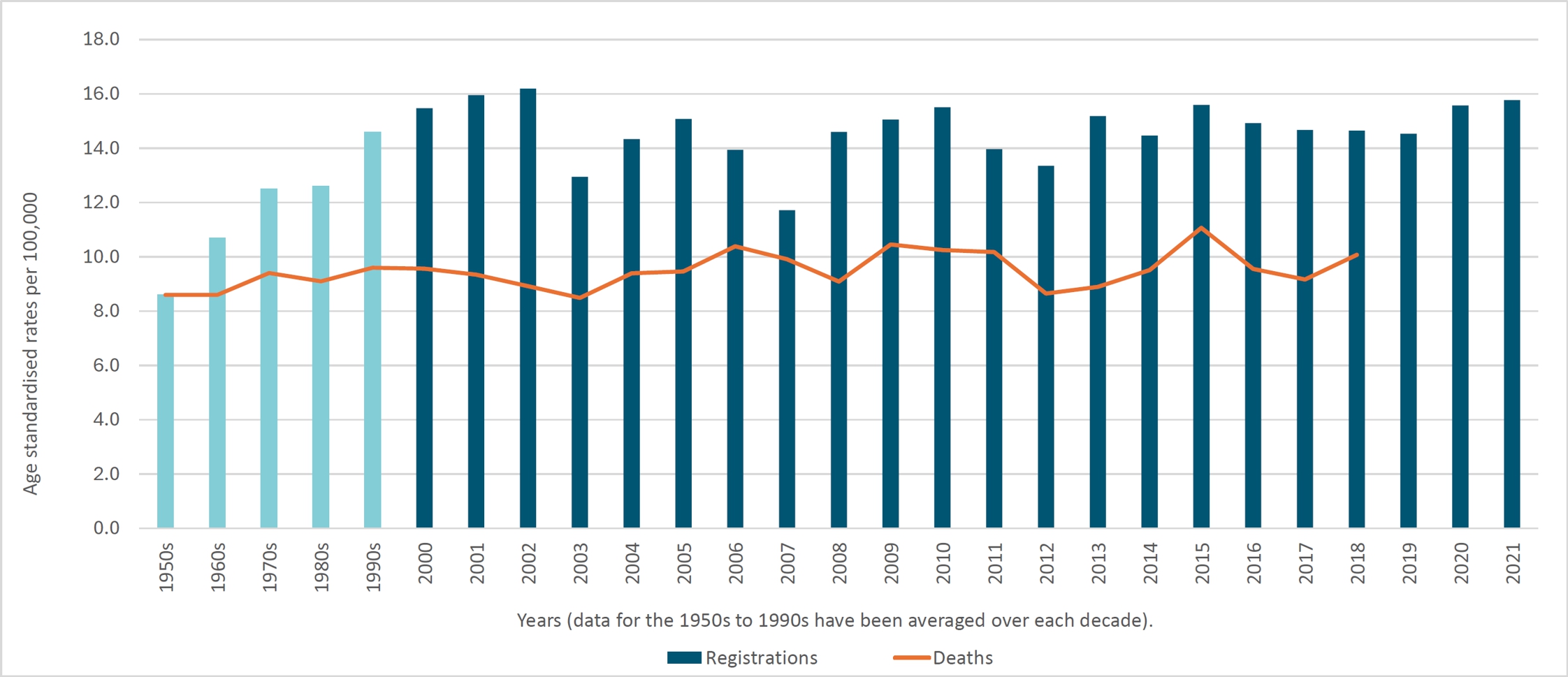

From 1948 when data was first collected, through to the late 1990s, there was a steady increase in the number of ovarian cancer diagnoses.[35] From 2000 to 2021 there has been fluctuation in the rate of diagnoses per 100,00 women, but there was no significant increase in the incidence of ovarian cancer. Similarly, the death rate since 2000 has fluctuated but the overall change is very low, perhaps insignificant, with an increase of about 0.5 women/wāhine per 100,000.

However, the number of deaths does not provide the complete picture. What is as important in the context of ovarian cancer deaths is the mortality rate, and these statistics are depressing.

Only pancreatic cancer and lung cancer have a higher mortality rate. On absolute numbers, ovarian cancer claims fourth place, but based on the mortality rate, it is the third biggest cancer killer of women/wāhine. The number of deaths each year over the twenty years to 2018 (the last year for which cancer death data is available) expressed as a percentage of the number of new diagnoses in that year shows that only pancreatic (90%)*** and lung cancer (80%)*** have a higher average death rate in women/wāhine than ovarian cancer (66%).

It is important to note that this is a somewhat crude calculation because there is a variable delay between diagnosis and death, so the deaths in any given year are unlikely to be among those diagnosed in the same year; however, these figures give us a decent indication of the percentage mortality.

Age

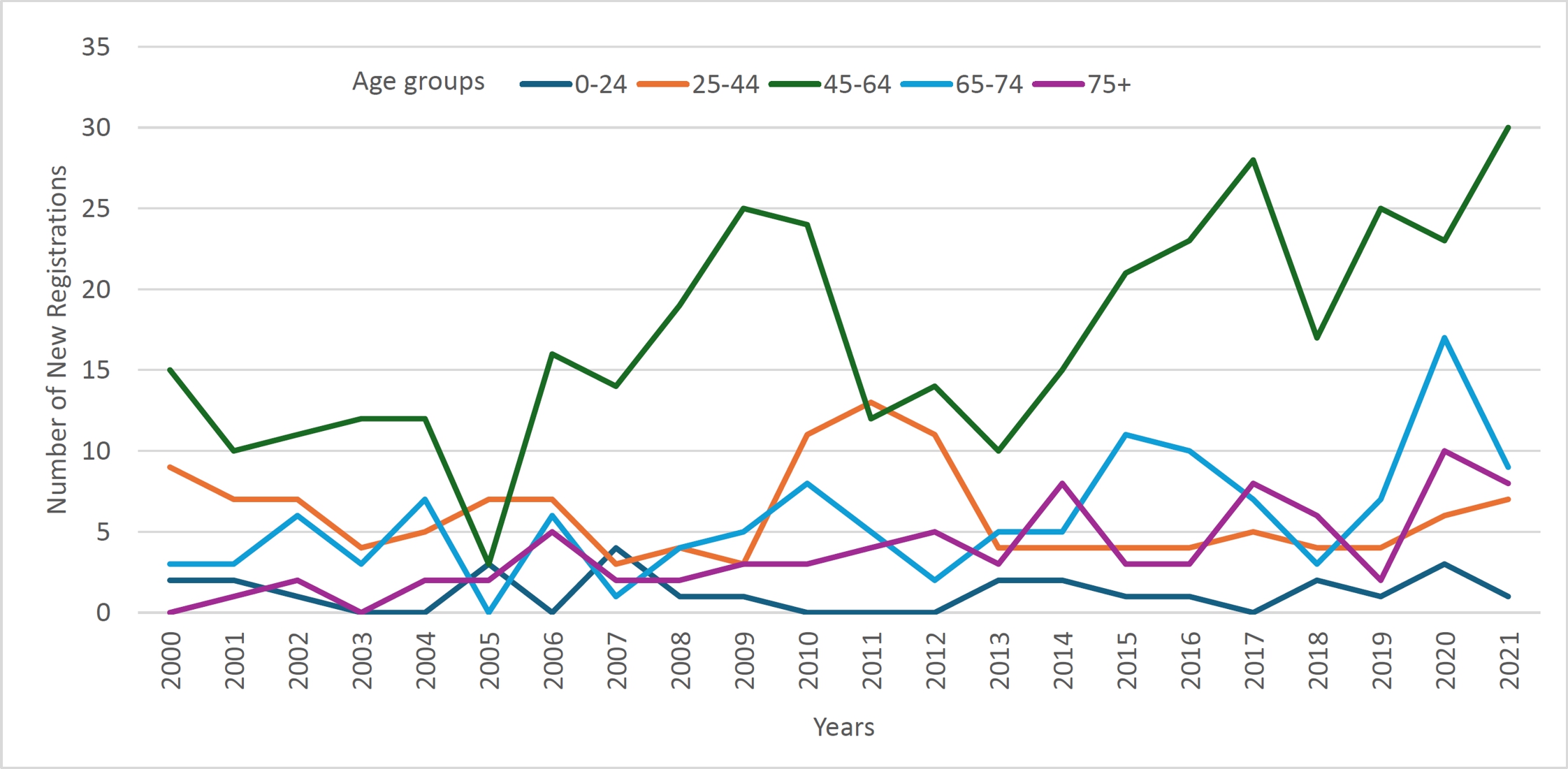

From 2000 to 2021, we can see that incidence of ovarian cancer has remained relatively consistent across the various age groups over time; there have been no sudden changes in incidence, just relatively small variations from year to year. Incidence is consistently highest in perimenopausal and menopausal women (45-64), followed by women of 75 years and over. This latter group is significant as the number of women in this age group is naturally smaller than in younger age groups, for example, in the 2018 census there were 170,604 women 75 years and over, while in the 45-64 year old age group there were 613,377.

Ovarian cancer is not common, but cannot be described as rare either, in the 25-44 year age group, with an average of 32 diagnoses in this group between 2012 and 2019. However, it is rare in the under 25s with an average of seven diagnoses per year.

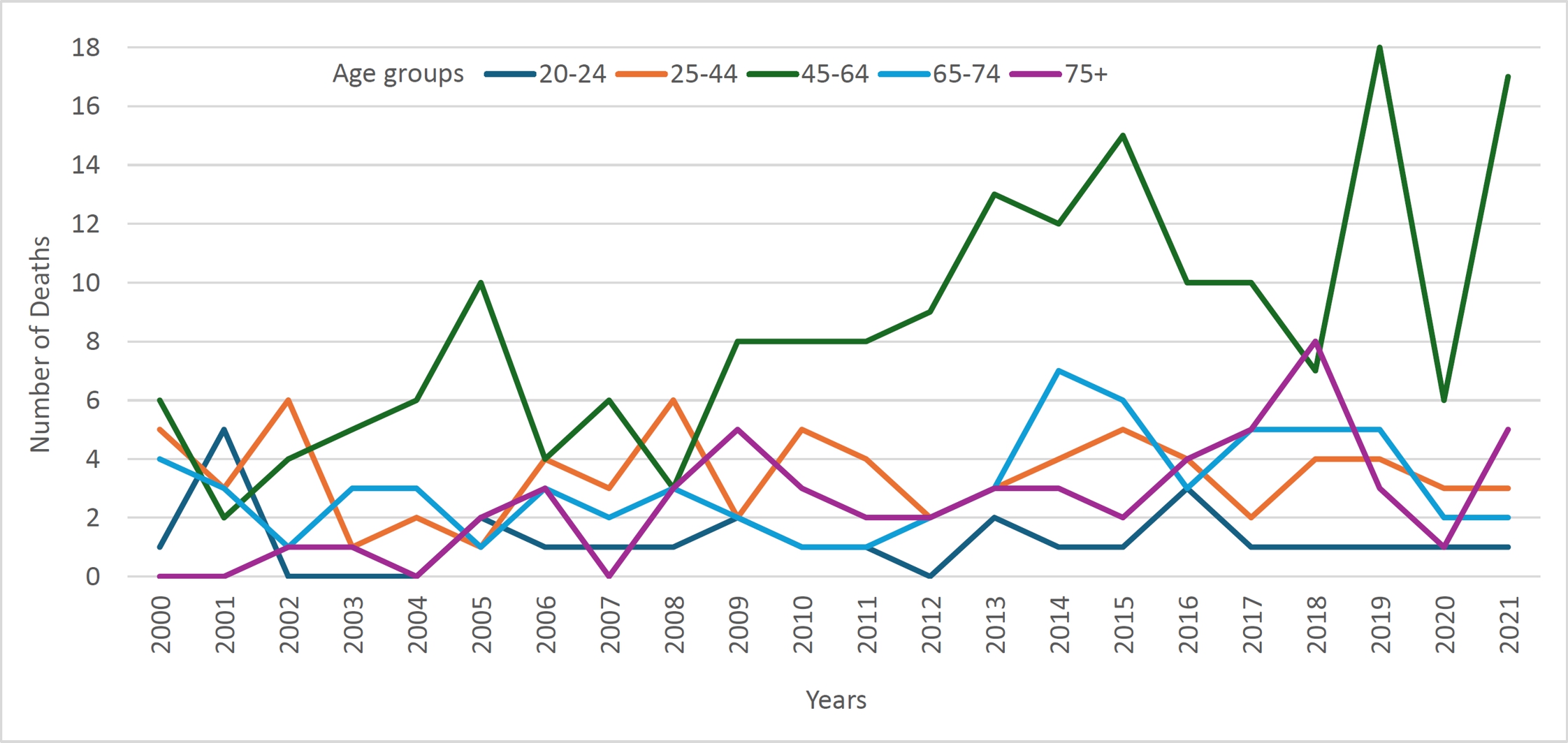

Deaths are highest in the over 75 age group, followed by 45-64 years and 65-74 years. Death is rare in under 25s, with fewer than one death per year.

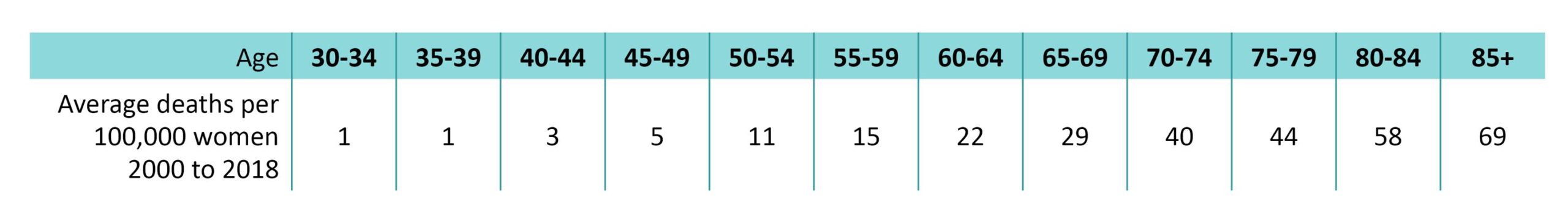

Deaths per 100,000 women/wāhine in each age group is a more accurate way of considering mortality, as the numbers of women/wāhine in each age group may vary considerably as the population ages. Age-standardised death rates show a steady increase in deaths per 100,000 women in each five year age group from 30 years of age up to 85+, with the death rate increasing more rapidly as the population ages.[35]

Ovarian Cancer in Wāhine Māori and Pāsifika

In research for this article, data provided by Health New Zealand, data available on the online Cancer Web Tool,[36] and the medical literature, were considered in order to gain an understanding of how wāhine Māori and Pāsifika are impacted by ovarian cancer.

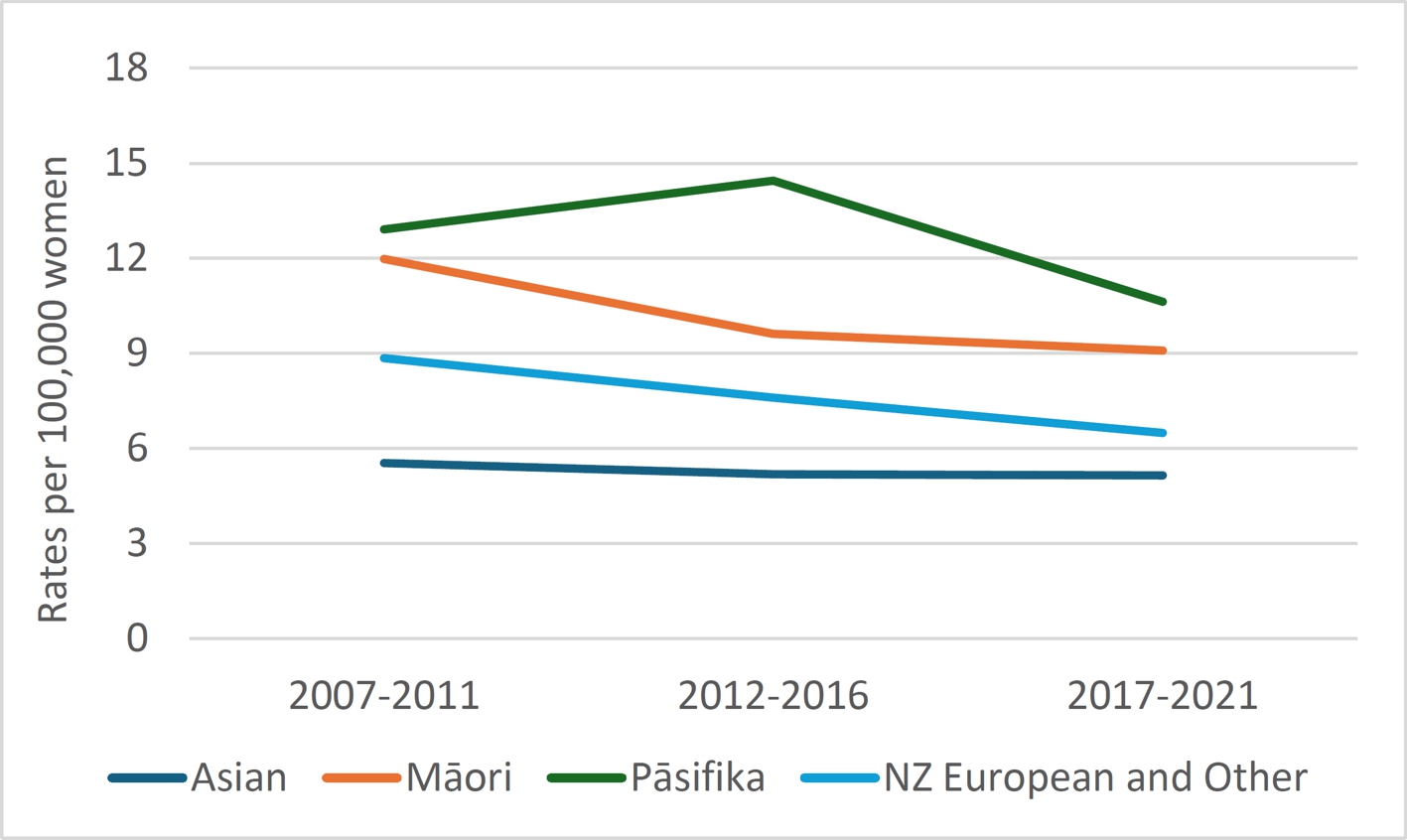

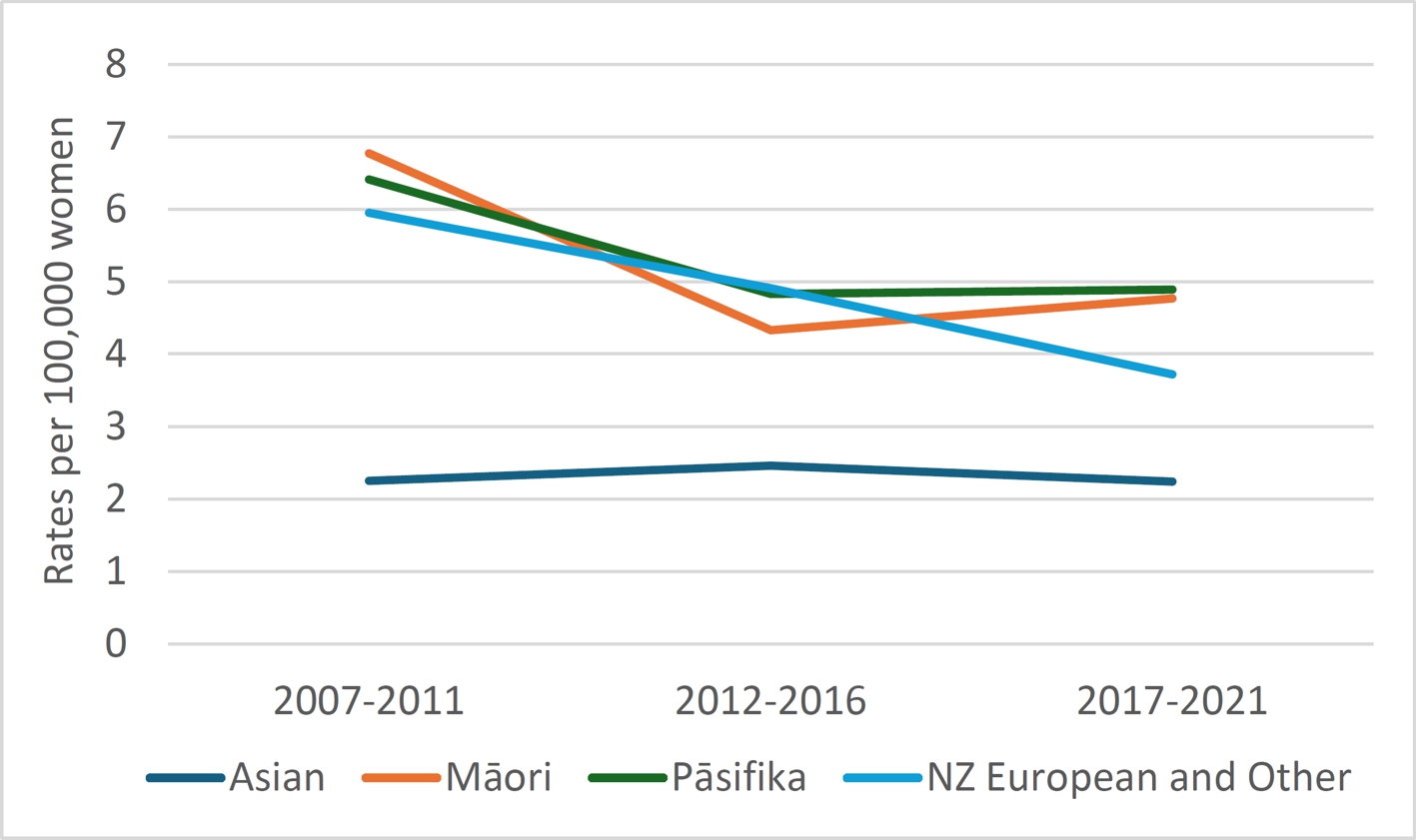

It is difficult to obtain a clear picture of the impact of ovarian cancer on wāhine Māori and Pāsifika; that is whether or not incidence and mortality is significantly higher than for non-Māori, non-Pāsifika, or not. Data provided by Health New Zealand includes cancer of the ovary and other uterine adnexa – a wider category than just cancer of the ovary.[35] The data on incidence and mortality by ethnicity that is available on the Cancer Web Tool[36] includes only ovarian cancer but is provided over five-year periods rather than year by year.

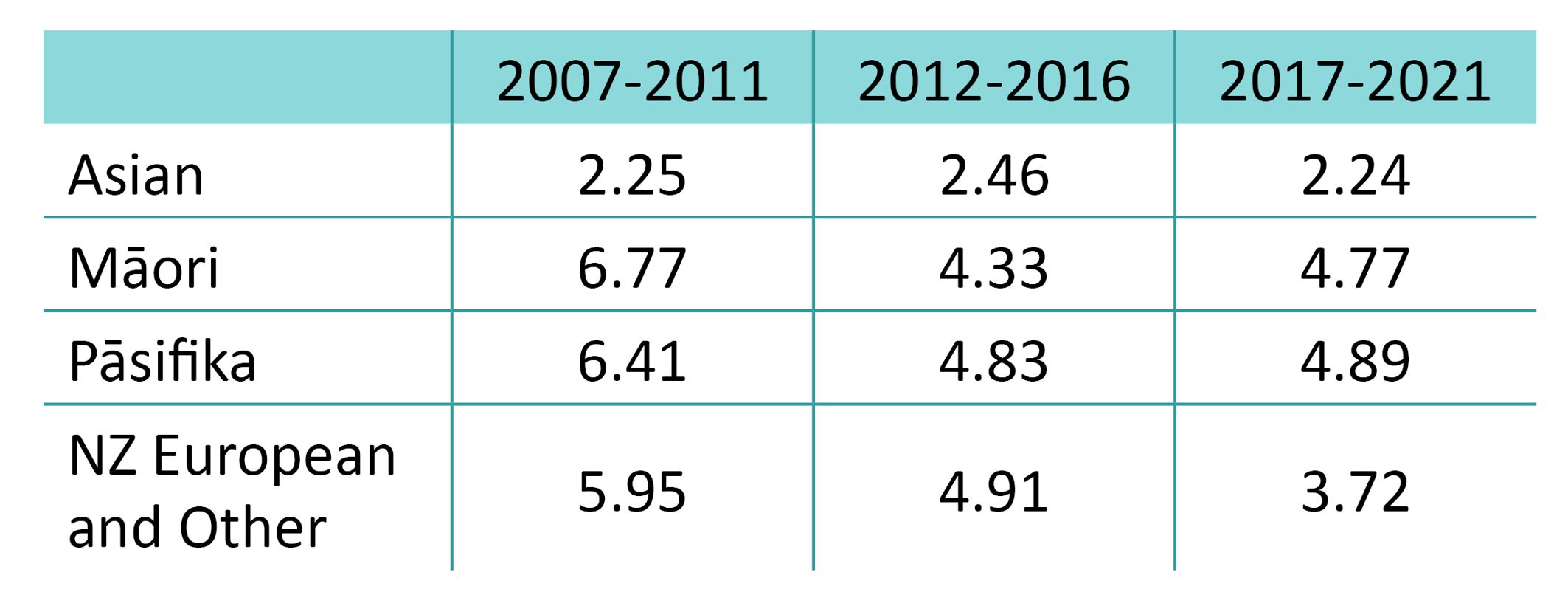

The two graphs to the right provide incidence of and deaths from ovarian cancer by ethnicity per 100,000 women over the last fifteen years of data in periods of five years. Whine Pāsifika have the highest incidence of ovarian cancer and Asian women the lowest. This is consistent with the findings of researchers from the Centre for Public Health Research, Massey University, who analysed data on all women registered with ovarian cancer on the New Zealand Cancer Registry between 1993 and 2004, for a 2009 paper in the Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health.[37] They found that the incidence of ovarian cancer was highest in wāhine Pasifika, intermediate in wāhine Māori, and lowest in non-Māori, non-Pasifika women; mortality rates showed the same pattern. However, the more recent data available shows a more complicated pattern of mortality, with a significant decline in mortality from 2007-2011 to 2017-2021 according to the Cancer Web Tool36, with mortality for both wāhine Māori and Pāsifika dropping below that of European and other women in 2012-2016, only to rise slightly in 2017-2021.

Cleverly et al. found, in a 2023 paper in the New Zealand Medical Journal, that survival rates among Pāsifika wāhine were considerably better than European women at one year (Pāsifika 74% vs European 67%), three years (54% vs 42%) and five years (48 vs 33%).[38] Sadly, five-year survival is appallingly low for both Pāsifika and European women.

Jefferys et al., wrote in a 2005 paper that there was improved five-year survival rates among wāhine Māori (60%) and Pāsifika (51%) compared to non-Māori/non-Pāsifika women (42%).[39] They concluded that the “apparent survival advantage among Māori for ovarian cancer was fully explained by stage at diagnosis,” that is, that Māori were being diagnosed earlier, leading to better outcomes.

They did not offer any explanation for why wāhine Māori might be diagnosed earlier, especially as they did point out the inequities faced by Māori in accessing health care “and that Māori are medically under-served in New Zealand”, factors which one would assume would disadvantage early diagnosis among Māori and therefore reduce survival rates. However, they did suggest that “[s]elective migration of terminally ill Pacific cancer patients to the Pacific would artificially inflate their survival rate [in New Zealand],” which may explain some of their results.

While a 2020 paper by Gurney et al., found that wāhine Māori with ovarian cancer are 62% percent more likely to die than non-Māori women[40] this may be strongly influenced by the much lower mortality rate among Asian women. When compared with the mortality rate of New Zealand European and other women (MELAA – Middle Eastern/Latin American/African), the data provided by the Cancer Web Tool shows that between 2007 and 2021, Māori mortality was only 14% higher in the years 2007-2011, 12% lower in the years 2012-2016, and 28% higher in the years 2017-2021, than mortality in women of New Zealand European and MELAA ethnicity.

Ovarian cancer registrations and deaths from 1950 to 2021. Please note: data for the decades 1950s to 1990s that data has been averaged over the decade; death data was only available from 1955 to 2018. Analysis of source data from Health New Zealand.[35]

Ovarian cancer registrations by age group 2000 to 2021. Source: New Zealand Cancer Registry data provided as Excel tables of cancer registration and deaths numbers and rates for malignant neoplasm of the ovary and other uterine adnexa.[35]

Ovarian cancer deaths by age group 2000 to 2021. Source: New Zealand Cancer Registry data provided as Excel tables of cancer registration and deaths numbers and rates for malignant neoplasm of the ovary and other uterine adnexa.[35]

Age-standardised death rates for ovarian cancer per 100,000 women in each age group from 30 to 85+ years from 2000 to 2018. Source: New Zealand Cancer Registry data provided as Excel tables of cancer registration and deaths numbers and rates for malignant neoplasm of the ovary and other uterine adnexa.35

Age standardised ovarian cancer registrations per 100,000 by ethnicity 2007 to 2021. Source: Cancer Web Tool.[36]

Age standardised ovarian cancer deaths per 100,000 by ethnicity 2007 to 2021. Source: Cancer Web Tool.[36]

Mortality rates for ovarian cancer per 100,000 of population in Asian, Māori, Pāsifika, and NZ European and other ethnicities from 2007-2021. Source: Cancer Web Tool.[36]

The researchers from Massey University’s Centre for Public Health Research,[37] found that there was no significant association between socioeconomic deprivation and tumour grade or stage. Wāhine Māori were more likely to be diagnosed earlier and seemed to have better prognostic factors. The average age at diagnosis was also lower in wāhine Pāsifika and Māori.

Some research suggests that while ovarian cancer incidence increases with age among women of European/Caucasian descent, women from non-European ethnicities may have higher incidence at younger ages.[21] A review of the data from Health New Zealand tables[35] for numbers of new diagnoses appears to show a trend consistent with those findings.

However, when the age standardised rates per 100,000 women are considered, it seems that the rates are indeed much higher for wāhine Māori in the older age groups; it is simply that the number of women between 64 and 74, and over 75 years of age are much smaller than the general population; life expectancy for wāhine Māori women is lower than for all other ethnicities in Aotearoa New Zealand.[41] For example, for every 100,000 Māori girls born, at age 65 on average only 82,892 will still be alive compared with 93,327 women of European descent. At age 75 the average is 63,617 and 84,425 respectively and at 85 years it is 33,483 for Māori and 59,409 for women of European descent.[42] The preponderance of diagnoses in younger wāhine Māori may well be simply because more wāhine die before they reach old age when the risk of ovarian cancer is highest.

From to 1998 to 2018 the mortality rate in wāhine Māori was about 53%. Again, this is a crude indicator of the mortality rate as there is a variable delay between diagnosis and death, so the deaths in any given year are unlikely to be among those diagnosed in the same year.

Prognoses and Progress

A 2019 study found that compared with six other high-income countries (Denmark, Norway, Australia, UK, Ireland and Canada) New Zealand made poorer progress in cancer control (i.e. increased survival, decreased mortality and incidence) in ovarian cancer than all of the other study nations.[43]

Between 1995 and 2014, we had the lowest increase in five-year ovarian cancer survival at only a 4.4% increase in survival across all age groups, compared with the highest achievers Canada (10.2% increase in survival), the UK (9.8%) and Norway (9.2%).[43] We performed a little better in women under 75 years with a 5.9% increase in five-year survival (UK 12%; Denmark 11.2%; Ireland 11.1%). However, we went backwards in women over 75 with a 0.9% reduction in five-year survival between 1995 and 2014. Only Canada did worse at -2.7%, while all other countries improved survival in elderly women.[43]

Five-year survival rates for ovarian cancer in New Zealand women/wāhine under 75 hovers around 40%, while it is only about 16-18% for over 75s, while most of the other countries have seen a steady increase to, or close to, 50% survival at five years for those under 75.[43]

Aotearoa New Zealand lags behind other comparable countries in improving outcomes for women/wāhine with ovarian cancer in four major areas:3

- Preventable delays in ovarian cancer diagnosis: there needs to be greater awareness among both women/wāhine and GPs about the symptoms of ovarian cancer (as discussed in Ovarian Cancer: Types, Diagnosis, Treatment and Late Diagnosis).

- Better treatment: while many ovarian cancers cannot be cured, improved treatments and more funded treatments would increase survival. There are multiple drug treatments for different types of ovarian cancer funded in the UK and/or Australia that are not funded in Aotearoa New Zealand, including Niraparib, Olaparib, Rucaparib, Bevacizumab, Caelyx, and Trametinib. Some women pay privately for access to these drugs; those without the financial capability to pay privately go without.

- Limited clinical trials in which Aotearoa New Zealand women/wāhine are able to participate: the National Ovarian Cancer Report reveals that there are only five clinical trials running in this country – compared with 45 trials in Australia – meaning that few New Zealanders have access to the most up to date treatments.[3]

- Lack of research both here and internationally: while ovarian cancer is the leading cause of gynaecological cancer death, research is disproportionately under-funded in Aotearoa New Zealand and overseas, but research funding is worse off here than elsewhere. Since 2011, Australia has invested AUS$71 million in ovarian cancer research[45] while during the same period, through the Health Research Council, Aotearoa New Zealand invested a total of $18,000 in ovarian cancer-specific research.[3] A 2021 Te Aho o Te Kahu report found that research into ovarian cancer was significantly underfunded in Aotearoa New Zealand relative to its mortality rate compared with other cancers, such as breast, cervical and uterine cancer.[45] Since the publication of the National Ovarian Cancer Report in 2022, the Health Research Council has approved funding of almost $850,000 for research into new drug therapies for ovarian cancers,[46, 47]. Still millions of dollars short of the Australian research investment even allowing for the five times greater population.

The Ovarian Cancer Foundation Petition to Parliament

Jane Ludeman was diagnosed in 2017 with low-grade serous ovarian cancer – a rare and poorly survivable form. In 2021, she presented a 7000+ signature petition to Parliament calling for national diagnostic guidelines for ovarian cancer to be developed, better treatment options, and more government funding. At the time, a survey undertaken by Cure Our Ovarian Cancer* found that “90 percent of women could not name a single symptom of ovarian cancer before their diagnosis and most experienced significant difficulties in accessing the blood test and ultrasound required to find their cancer.”[48]

Jane Ludemann requested the support of the AWHC for their submissions to the Health Select Committee and sent us the Cure Our Ovarian Cancer National Ovarian Cancer Report.[3] The Report paints a disturbing and depressing picture of the situation for women/wāhine who develop ovarian cancer in this country. While there have been public awareness campaigns and screening programmes for breast and cervical cancer, awareness of ovarian cancer has barely seeped into the consciousness of the majority of New Zealanders. Twenty-five years of sufficient resourcing, awareness raising and a public screening programme for cervical cancer has resulted in a significant decline in the incidence of, and importantly, mortality from cervical cancer. Sadly, the same cannot be said for ovarian cancer, and as a result more than four times as many women die each year from this disease.

Researchers have identified a set of physical complaints that often occur in women who have ovarian cancer and may be early warning signs. While these symptoms are also common to other conditions, researchers believe that greater awareness will lead to earlier diagnosis and treatment, therefore reduced mortality.

All too often women presenting to their doctor with physical symptoms are fobbed off or diagnosed with functional or somatic disorders. Many common diseases and conditions take far too long to be diagnosed resulting in morbidity, disability, loss of quality of life, and in the case of diseases like ovarian cancer, a premature death. In a UK survey, 8% of women presenting with symptoms of ovarian cancer were told by their GP that their symptoms might be related to their mental health.[49] Another study found that diagnosis was impacted by “physicians’ stereotypes, prejudices and their preconceived notions regarding women.”[14]

We are far from a situation in which all women in this country have accessible, affordable, available, and culturally appropriate and acceptable healthcare. For women/wāhine who are Māori, Pāsifika, disabled or members of the LGBTQI+ community, the barriers and discrimination they face are multiplied. The statistics that Cure Our Ovarian Cancer present on ovarian cancer epitomise these issues.

The burden of undiagnosed, untreated ovarian cancer does not just fall on the woman who suffers considerable loss of quality of life and an avoidably premature death, but on their family/whānau and community. In addition, there is the loss of productive years, and a calculable burden on our health system when a woman/wāhine is diagnosed with advanced ovarian cancer.

In July 2023, the Ovarian Cancer Foundation NZ made an oral submission to the Parliamentary Health Select Committee and the Committee’s report was published in August 2023.[50] The report acknowledged there are issues with the diagnosis, treatment and research of ovarian cancer. In the report, the Health Select Committee made the following two recommendations:

- that ovarian cancer and uterine cancer symptoms education be included in the National Cervical Screening Programme, and they strongly encouraged Te Whatu Ora Health | New Zealand to investigate this as a possibility.

- that Te Aho o Te Kahu (Cancer Control Agency) work with other agencies to explore how they can measure the effectiveness of detection, diagnosis and treatments in ovarian cancer.

The Ovarian Cancer Foundation NZ have requested a meeting with the Minister of Health, Dr Shane Reti, to determine the next steps, and are hopeful that Aotearoa New Zealand will become the first country in the world to implement gynaecological cancer symptoms education into the National Cervical Screening Programme.

There will always be deaths from ovarian cancer, but if this disease is prioritised the way the cervical cancer has been, Aotearoa New Zealand could see a substantial increase in the numbers of women/wāhine living longer than five years after diagnosis.

Footnotes

‡ NZ data on ovarian cancer often includes “other uterine adnexa”. The adnexa is the region adjoining the uterus that contains the ovary and fallopian tube, as well as associated vessels, ligaments, and connective tissue. Additionally, “there is increasing evidence that much of what was traditionally thought of as ovarian or peritoneal cancer in fact originates in the fallopian tube. In this article the term “ovarian cancer” includes other uterine adnexa.

* Now known as the Ovarian Cancer Foundation NZ

* This author acknowledges that there are many other health and social factors to consider in make such lifestyle choices. This ‘ideal’ prevention strategy for ovarian cancer is based entirely on the evidence of risk factors not other health and social issues.

† surgical removal of fallopian tubes and ovaries.

*** (pancreatic and lung cancer data was derived from Te Whatu Ora’s Cancer Web Tool;[36] ovarian cancer data was derived from Health New Zealand tables[35]).

References

[1] Ovarian Cancer Foundation NZ, Symptoms of Ovarian Cancer

[2] Ebell MH, et al., 2016: A Systematic Review of Symptoms for the Diagnosis of Ovarian Cancer, American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2016 Mar;50(3):384-394.

[3] Cure Our Ovarian Cancer, 2022: National Ovarian Cancer Report: Steps To Save Lives, September 2022, Cure Our Ovarian Cancer: Dunedin NZ

[4] UW Medicine, 2022: Ovarian cancer is not a silent killer, Nortworthy, University of Washington, 15 January 2022.

[5] Goff B, 2022: Ovarian Cancer Is Not So Silent, Obstet Gynecol. 2022 Feb 1;139(2):155-156.

[6] Goldstein CL, et al., 2015: Awareness of symptoms and risk factors of ovarian cancer in a population of women and healthcare providers, Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2015 Apr;19(2):206-12.

[7] Nagle CM, et al., 2011: Reducing time to diagnosis does not improve outcomes for women with symptomatic ovarian cancer: a report from the Australian Ovarian Cancer Study Group, J Clin Oncol. 2011 Jun 1;29(16):2253-8.

[8] McPhail S, et al., 2022: Risk factors and prognostic implications of diagnosis of cancer within 30 days after an emergency hospital admission (emergency presentation): an International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership (ICBP) population-based study, Lancet Oncol. 2022 May;23(5):587-600.

[9] Ovarian Cancer Foundation NZ, About Ovarian Cancer

[10] Walker JL, et al., 2015: Society of Gynecologic Oncology recommendations for the prevention of ovarian cancer, Cancer. 2015 Jul 1;121(13):2108-20.

[11] Hanley GE, et al., 2022: Outcomes From Opportunistic Salpingectomy for Ovarian Cancer Prevention, JAMA Netw Open. 2022 Feb 1;5(2):e2147343.

[12] Goff B, 2022: Ovarian cancer is not a silent killer – recognizing its symptoms could help reduce misdiagnosis and late detection, The Conversation, April 26, 2022.

[13] TOC, 2022: Pathfinder 2022: Faster, further, and fairer, Target Ovarian Cancer.

[14] Vela‐Vallespín C, et al., 2023: Women’s experiences along the ovarian cancer diagnostic pathway in Catalonia: A qualitative study, Health Expectations. 2023 Feb; 26(1): 476–487.

[15] Ovarian Cancer Foundation NZ, Testing For Ovarian Cancer

[16] Stewart C, et al., 2019: Ovarian Cancer: An Integrated Review, Semin Oncol Nurs. 2019 Apr;35(2):151-156.

[17] Han CY, et al., 2024: Normal Risk Ovarian Screening Study: 21-Year Update, J Clin Oncol. 2024 Jan 9:JCO2300141..

[18] Dilley J, et al., 2020: Ovarian cancer symptoms, routes to diagnosis and survival – Population cohort study in the ‘no screen’ arm of the UK Collaborative Trial of Ovarian Cancer Screening (UKCTOCS), Gynecologic Oncology. 2020 Aug; 158(2): 316–322.

[19] Harvard Medical School, 2017: Certain symptoms may be early signs of ovarian cancer, Harvard Health Publishing, January 20, 2017.

[20] Sundar S, et al., 2015: Diagnosis of ovarian cancer, BMJ. 2015 Sep 1:351:h4443.

[21] Zayyan MS, 2020: Risk Factors for Ovarian Cancer, from Tumor Progression and Metastasis (Eds. Lasfar A and Cohen-Solal K). IntechOpen. Accessed at https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/70875

[22] Whelan E, et al., 2022: Risk Factors for Ovarian Cancer: An Umbrella Review of the Literature, Cancers (Basel) . 2022 May 30;14(11):2708.

[23] Ali AT, et al., 2023: Epidemiology and risk factors for ovarian cancer, Prz Menopauzalny. 2023 Jun; 22(2): 93–104.

[24] Yu L., et al., 2023: Ovulation induction drug and ovarian cancer: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis, J Ovarian Res. 2023 Jan 24;16(1):22.

[25] Webb PM, et al., 2017: Trends in hormone use and ovarian cancer incidence in US white and Australian women: implications for the future, Cancer Causes Control. 2017 May;28(5):365-370.

[26] Reid BM, et al., 2017: Epidemiology of ovarian cancer: a review, Cancer Biol Med. 2017 Feb;14(1):9-32.

[27] Burges A and Schmalfeldt B, 2011: Ovarian Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment, Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2011; 108(38): 635-41.

[28] Langseth H, et al., 2008: Perineal use of talc and risk of ovarian cancer. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2008;62:358–60.

[29] Cramer DW, et al., 2016: The Association Between Talc Use and Ovarian Cancer: A Retrospective Case-Control Study in Two US States, Epidemiology. 2016 May;27(3):334-46.

[30] Buys SS, et al., 2011: Effect of screening on ovarian cancer mortality: the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA, 2011 Jun 8;305(22):2295-303.

31] Chien J and Poole EM, 2017: Ovarian Cancer Prevention, Screening, and Early Detection: Report From the 11th Biennial Ovarian Cancer Research Symposium; Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2017 Nov;27(9S Suppl 5):S20-S22.

[32] Menon U, et al., Mortality impact, risks, and benefits of general population screening for ovarian cancer: the UKCTOCS randomised controlled trial, Health Technol Assess. 2023 May 11:1-81.

[33] Gupta KK, et al., 2019: Ovarian cancer: screening and future directions. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2019 Jan;29(1):195-200.

[34] USPSTF, 2018: Screening for Ovarian Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement, JAMA. 2018;319(6):588-594.

[35] New Zealand Cancer Registry data provided as Excel tables of cancer registration and deaths numbers and rates for malignant neoplasm of the ovary and other uterine adnexa. Provided in a personal communication by C. Lewis, Senior Information Analyst, Health New Zealand on the 19th of March 2024.

[36] TWO: Cancer Web Tool, Te Whatu Ora, accessed on 14 March 2024

[37] Firestone RT, et al., 2009: Characteristics of ovarian cancer in women residing in Aotearoa, New Zealand: 1993-2004. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2009 Oct;63(10):814-9.

[38] Cleverly T, et al., 2023: Cancer incidence, mortality and survival for Pacific Peoples in Aotearoa New Zealand, N Z Med J. 2023 Dec 1;136(1586):12-31.

[39] Jeffrys M, et al., 2005: Ethnic Inequalities in Cancer Survival in New Zealand: Linkage Study, Am J Public Health. 2005 May; 95(5): 834–837.

[40] Gurney J, et al., 2020: Disparities in cancer-specific survival between Māori and non-Māori New Zealanders, 2007–2016. JCO Global Oncology (6): 766–74.

[41] Stats NZ, 2021: Growth in life expectancy slows, 20 April, 2021.

[42] Stats NZ, 2021: New Zealand period life tables: 2017–2019, 20 April 2021.

[43] Arnold M, et al., 2019: Progress in cancer survival, mortality, and incidence in seven high-income countries 1995-2014 (ICBP SURVMARK-2): a population-based study, Lancet Oncology, 2019 Nov;20(11):1493-1505.

[44] Hunt G, 2021: Increasing ovarian cancer care and support, Department of Health and Aged Care, Media Release16 February 2021

[45] Te Aho o Te Kahu, 2021: He Pūrongo Mate Pukupuku o Aotearoa 2020, The State of Cancer in New Zealand 2020. Wellington: Te Aho o Te Kahu, Cancer Control Agency.

[46] HRC, 2023: Novel targeted therapeutic strategy for ovarian cancer treatment, Health Research Council NZ.

[47] HRC, 2024: Multi-Drug Antibody-Drug Conjugates for Targeted Cancer Therapy, Health Research Council NZ.

[48] Hatton E, 2021: Ovarian cancer petition: Thousands call for better diagnosis, funding, Radio New Zealand, 17 March 2017.

[49] TOC, 2016: Pathfinder 2016 – transforming futures for women with ovarian cancer, Target Ovarian Cancer 2016.

[50] Personal Communication from Holly Townsend, Operations Coordinator, Ovarian Cancer Foundation NZ